By Swayne Martin

Boldmerhod (www.boldmethod.com)

The following report was published by a CFI to the NASA ASRS reporting database

Have you heard of the “chop and drop” short field landing? Here’s what you need to know, so you don’t end up in a ditch like these two pilots.

An Unstable Approach, And Sudden Airspeed Increase

I was CFI during a BFR. The student, who is a private pilot, was the pilot flying (PF). Winds (5 miles away) were reported as 310 degrees at 17, gusting 27 knots. The PF stated he was going to use flaps 20 and higher speed than normal for the approach and landing.

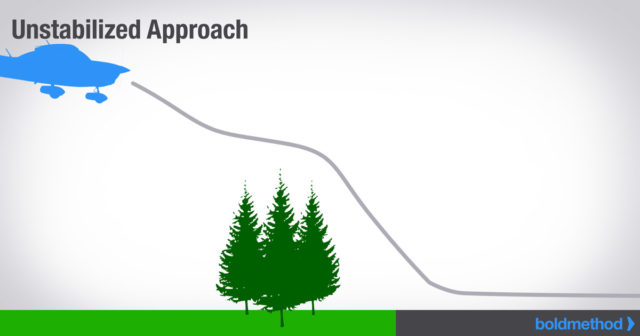

The aircraft cleared the trees at the end of the runway, then the PF chopped the power and pitched the aircraft down towards the runway. Airspeed increased and when he flared the aircraft started floating down the runway. He finally touched down a little past 1/2 way down the runway with brakes applied.

The aircraft was skidding. A few moments later a gust of wind lifted the right wing, thus reducing braking. I looked ahead to consider a balked landing and saw power lines and a tree which I believed we would hit should a go-around be initiated. We went off the end of the runway, through a ditch, and came to stop on a road at the end of the runway. There was damage to the aircraft’s nose wheel, prop, and left wing tip. Both of us were unhurt.

What Went Wrong?

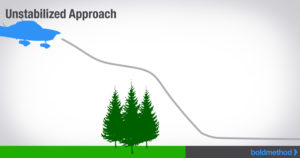

As the pilot flew over trees at the end of the runway, he chopped the power and pitched down. He most likely thought (or hoped) that his airspeed wouldn’t accelerate further, because the power was reduced to idle. But since they were flying with less flaps, there was less drag to control their steep descent.

In this landing, the pilot was already carrying more airspeed because of the gusting headwind. As they pitched down after cross the obstacle, airspeed increased even more, leading to excessive floating and the runway overrun.

The Solution? Fly A Constant Descent Angle

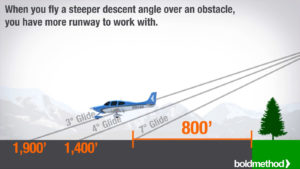

If you have an obstacle at the approach end of the runway, you should fly a constant rate, steeper-than-normal approach. By flying a slightly steeper angle, you can safely clear the obstacle, and not use up too much runway before you touch down. The steeper your glide path, the more runway you have available to touch down. And by flying a constant rate descent, as opposed to a “chop and drop” approach after you’ve cleared an obstacle, you’ll maintain stable airspeed all the way to the runway.

On the topic of airspeed, in gusty conditions, flying a slightly faster airspeed on approach is a good idea. In most cases, adding half the gust factor to your final approach speed is the recommended procedure. In this case, with winds at 17 knots, gusting to 27, adding 5 knots to final approach speed would have been appropriate. While we don’t know how fast the pilot flew final, it’s possible he added more the 5 knots to their final approach speed, exacerbating the float/overrun situation.

But flying a steeper approach has its disadvantages too. Since you’re flying a steeper descent angle, and you have a high-than-normal descent rate, judging your flare is harder. You’ll need to pitch up more in the flare to arrest your descent rate for a smooth touchdown.

Timing the flare on a short field landing really comes down to practice. Flare too late, and you’ll land hard. Flare too early, and you can stall early and develop a large sink rate. Neither scenario is good, and the best way to avoid either one is to practice (Read more on short field landing and flare technique here.)

Finally, picking a go-around point on a short field approach is essential. As the CFI mentioned in the report, floating too far down the runway eliminated their option for a safe go-around. Had they initiated a go-around earlier, for instance, once they crossed the first third of the runway, it’s likely the overrun could’ve been avoided altogether.